Forgotten Murals II: Art Casualty of Built History

Following on from Forgotten Murals of the Adelaide Children’s Hospital (2018), this exhibition sketches the life story of another significant large-scale artwork to emerge from the Women’s and Children’s Hospital archives.

The mural relief was designed by architect Reginald Steele for the General Purposes Building at the old Children’s Hospital. Prominently occupying the building’s upper southern façade, it watched over the entrance to the Casualty Department. Measuring 78 by 14 feet and cast in concrete with raised abstract motifs, the Modernist artwork attracted mild disapproval upon its public debut in December 1962.

The artwork led a chequered life – or lives. Surviving one demolition in 1976, its second life was a much reduced, semi-subterranean existence. Ahead of a major site redevelopment to accommodate the Queen Victoria Hospital on the North Adelaide site, a second target was placed on its back. In 1992 the wrecking ball swung again. The downfall was total. The mural became a footnote of art history: an art casualty of built history.

With appreciation among Adelaideans for local Modernist design at a retrospective high, Forgotten Murals II reappraises Steele’s bold creation – an intriguing Arts-in-Health offering for the Hospital’s child patients and maintenance workers.

Read the Curator’s essay here: Forgotten Murals II: Art Casualty of Built History – Curator Essay.

View the exhibition brochure here: Forgotten Murals II: Art Casualty of Built History – Exhibition Catalogue.

The building with the bold face

The life story of the artwork to which this exhibition is dedicated begins in 1955. After three decades of negotiation, the Adelaide Children’s Hospital succeeded in purchasing the North Adelaide land on the corner of Kermode Street and Sir Edwin Smith Avenue that was occupied by St Peter’s Girls’ School. It was finally able to progress its major development goal to construct a modern, multi-storey Outpatients block.

Architects for the local firm Woods, Bagot, Laybourne-Smith and Irwin (now Woods Bagot) were contracted to draw up various future site development schemes (1956–59). An extensive Building Appeal was mounted to help fund the works.

The operations of the proposed Outpatients block required two supporting buildings to be constructed close by: (1) a boiler house; and (2) a building to host a power plant, emergency generator and maintenance services. This exhibition focuses on the latter: the GPB (General Purposes Building).

For a building with vital functions, the GPB has a very low profile in the built history of the Hospital. During its short life it was known by an assortment of other non-distinguished names, such as ‘maintenance services building’, ‘workshop building’ and ‘general services block’. Visually, however, the GPB was no shrinking violet. The building’s southern face was distinguished with an eye-catching, sculptural mural designed by its architect, Reginald Steele (1911–84).

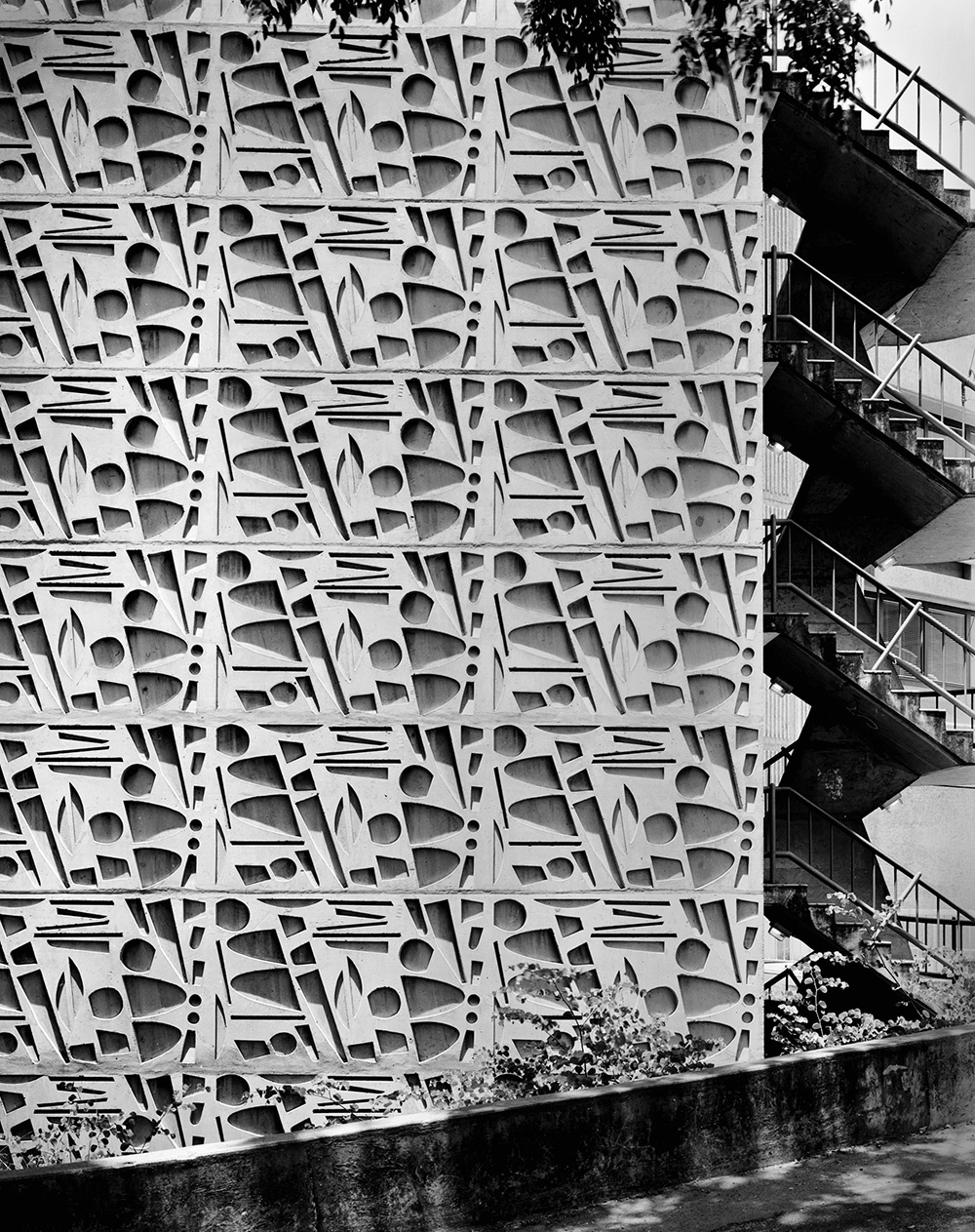

This (untitled) mural relief was no wallflower either. Firstly: it was not bolted to the building wall. It was the building wall. Secondly: it was bold in both design and scale, measuring at 78 by 14 feet (23 x 4 m). Despite its grand size, there are few known photographs of the artwork. It was difficult to capture in its entirety. Throughout this exhibition, it is ‘shown’ either in partial view or *just* out of shot.

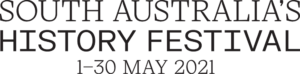

Clarence Rieger (Outpatients) Building, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, mid-late 1960s

The General Purposes Building (GPB) was built to serve the Hospital’s multi-storey Outpatients block, and lived in its shadow.

In this view from Peace Park on Sir Edwin Avenue, one end of the mural relief on the GPB is just visible on the right, above a moving car. In all other known photographs taken from this angle, the artwork is completely obscured by a tree.

General Purposes Building with partial view of mural relief, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, c1976

Collectively, the 38 panels of Reginald Steele’s mural sculpture comprised an upper structural wall on one end of the General Purposes Building. The rest of the structure was built using the same salmon-coloured brick as can be seen on the rear and sides of the Clarence Rieger (Outpatients) Building which still stands on Kermode Street today.

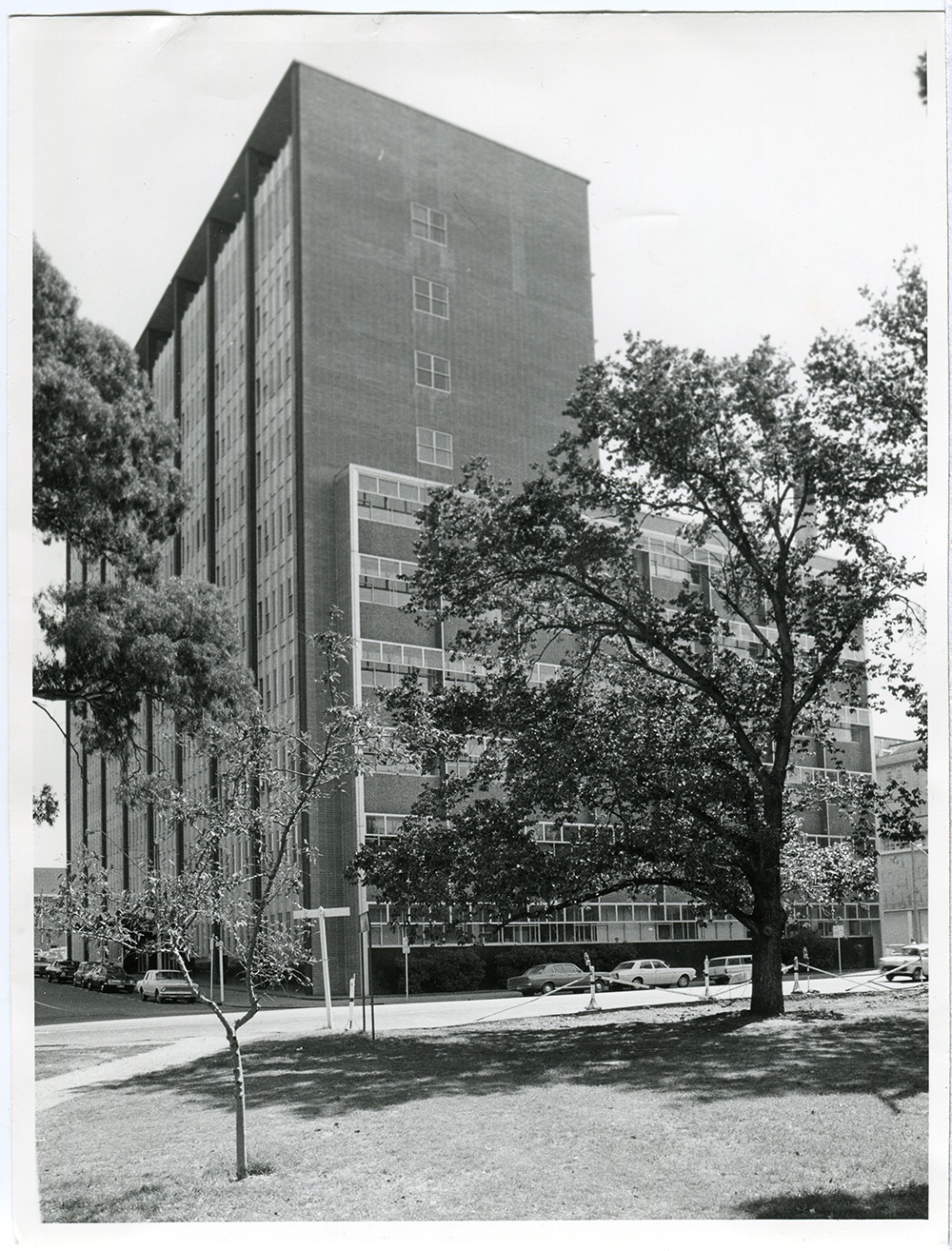

Aerial view of North Adelaide showing Adelaide Children’s Hospital, c1971

The General Purposes Building with the mural sculpture is in shadow, situated in the dip between the 11-storey Outpatients Building and the Boiler House with the tall chimney stack.

Source: Original photograph by D. Darian Smith, CA 1233/1

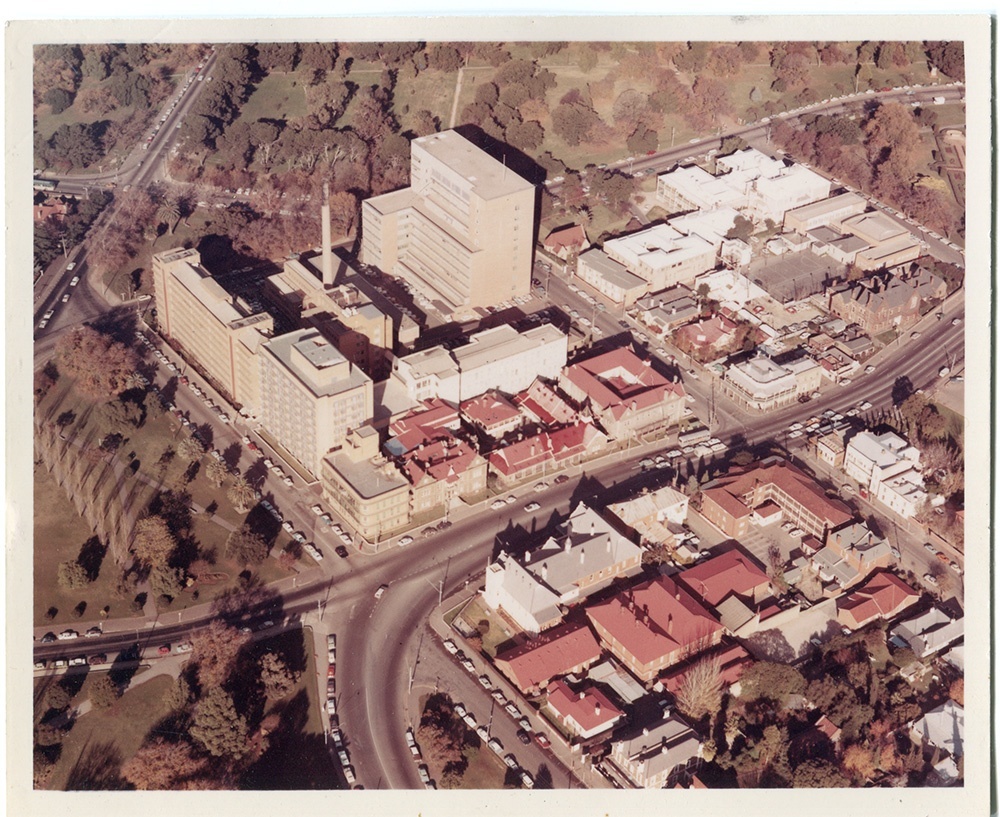

Adelaide Children’s Hospital Future Development Plan, Scheme ‘C’, 9 June 1963

On this plan, the General Purposes Building is shown connected to the Casualty Department by a diagonal tunnel. The surgical block facing Kermode Street was not approved.

Plan prepared by Woods, Bagot, Laybourne-Smith and Irwin Architects, Job No. 1490, Drawing No. 10.

Architectural model of Adelaide Children’s Hospital, c1967

This 3-D model was constructed by Woods Bagot architects to demonstrate a proposed design for Hospital expansion works. The City of Adelaide Development Committee rejected this model in the early 1970s, due to concerns about the visual impact of extending the Outpatients Building further along Kermode Street at the same height.

The little General Purposes Building behind Outpatients is marked with a simple grid of 38 panels to represent Reginald Steele’s complex mural design.

The man behind the mural relief

The creator of this curious mural, Reginald Goodman Steele, was born on 2 March 1911 in Glenelg. He was the youngest child of Vivien Grace Steele (née Stock) and William Steele; a notable businessman and Director of the SA Gas Company (1935–) and the Bank of Adelaide (1936–).

Reginald Steele attended St Peter’s College. From 1928 to 1932 he studied at the SA School of Mines and Industries (now the University of South Australia) and completed his articles with the architectural firm Woods, Bagot, Laybourne-Smith and Irwin. As part of this training he took classes at the SA School of Arts and Crafts with notable alumni Victor Adolfsson, John Dowie and Geoff Shedley.

In 1933 Steele won a design competition with colleagues (Sir) James Irwin and Gordon Laybourne-Smith to build the original Gilbert Wing of the Adelaide Children’s Hospital. Around the mid-1930s he undertook some architectural study in Italy. He married Miss Lynn Drury of Elsternwick (Melbourne) in 1937 and settled in Walkerville.

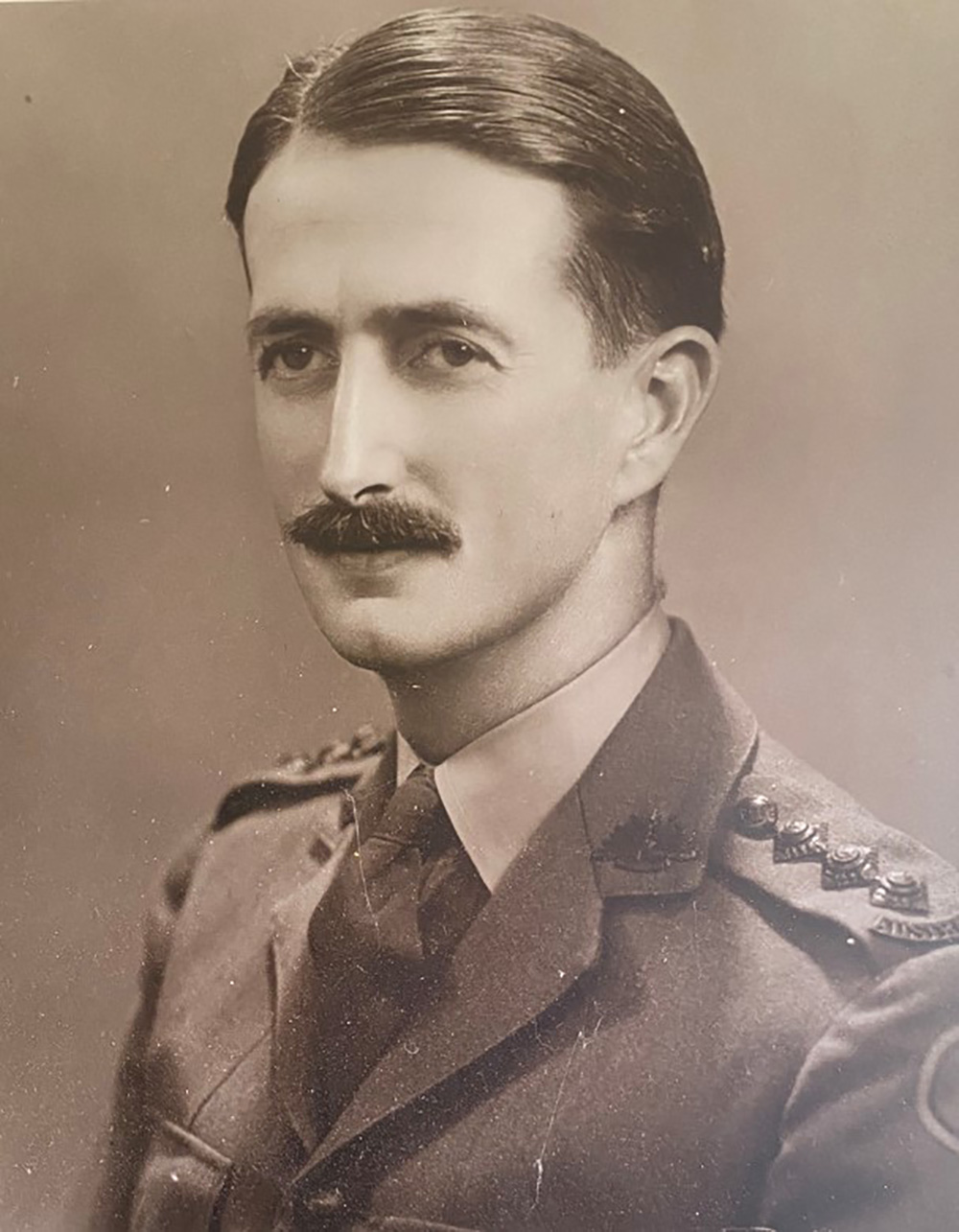

Enlisted in World War II (1942–46), Steele served in the 13th Australian Field Regiment (Jungle Division) of the Royal Australian Artillery (Field) in the Australian Imperial Force. Steele resumed practising as an architect upon his return. From the late 1940s he taught design at the School of Mines and Industries.

Reginald Steele contributed to a number of design projects for the Adelaide Children’s Hospital until his retirement from Woods Bagot in the 1970s. He was succeeded at the firm by his youngest son, William (Bill) Steele who – among his many local and international achievements in architecture – took executive charge of the major redevelopment of the Children’s Hospital site in the 1970s.

Portrait of Lieutenant Reginald Goodman Steele, c1942–46

Source: Courtesy of William Steele

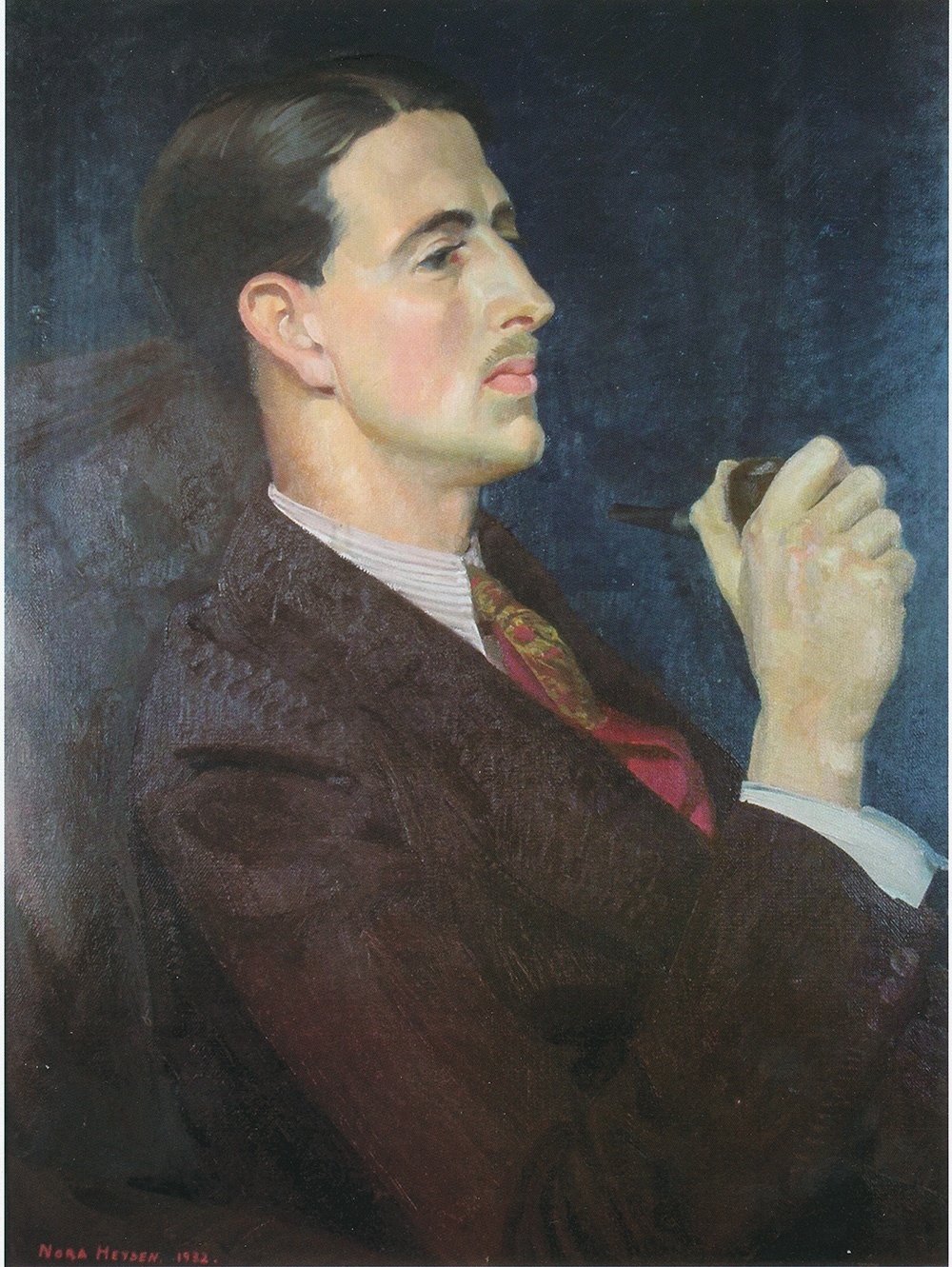

Nora Heysen, Portrait, Reginald Goodman Steele, oil on canvas, 62 x 45 cm, 1932

Intriguingly, Reginald Steele had his portrait painted by acclaimed artist Nora Heysen (1911–2003) in 1932. One of two commissioned portraits she completed that year, the finished work was loaned for an exhibition of the South Australian Society of Arts in October. On the back is an inscription written by Reginald’s wife Lynn:

This loved picture … it is of the greatest comfort to me in this awful war with my loved in terrible danger on active service in Papua.

The oil painting is currently in private hands (owner unknown).

Source: Original entry in Elder Fine Art auction catalogue, 7 May 2006

Reginald Steele with friends at a cocktail party, 28 November 1936

This illustration published in an Adelaide social column depicts Steele attending a cocktail party thrown by Mr Bob and Mrs Moxham Graham at their Burnside home to welcome him back from Italy, where he had been studying architecture. Flanking the man of the hour is Miss Rowena Bray (at left), and Miss Mary Kyffin Thomas.

Source: ‘Diana’s Notebook’, Mail (Adelaide), p. 19

The mild controversy

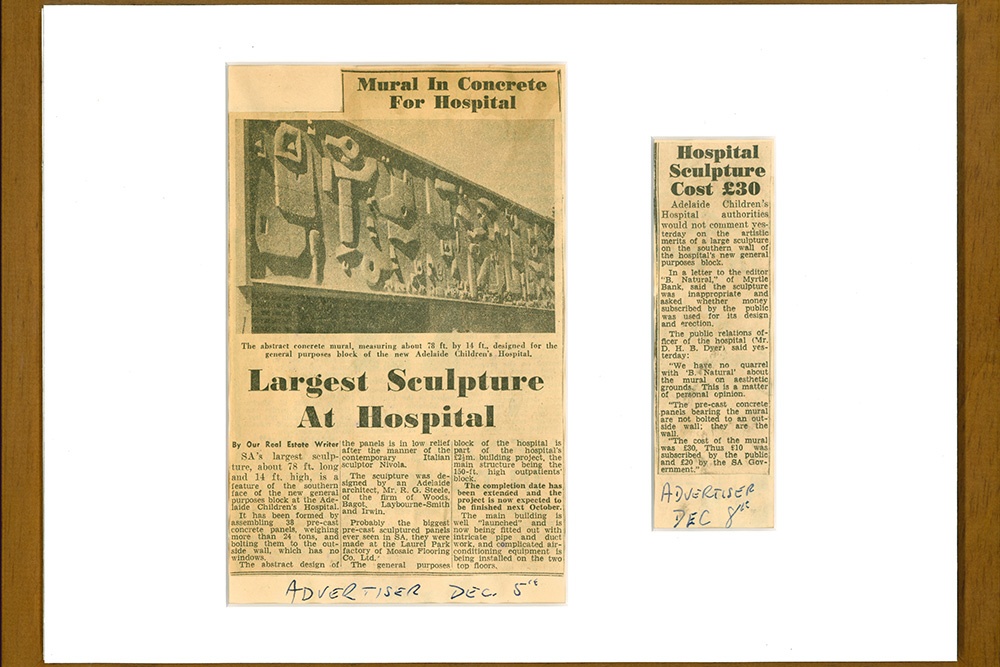

Reginald Steele’s sculpture made its public debut in a local newspaper article on 5 December 1962. The informant was probably Steele himself, as it contains a key clue to the inspiration behind his design and choice of medium for the artwork.

The mural is significant. Comprised of 38 precast panels, each measuring 2.1 x 1.2 m, it was allegedly the largest sculpture made to date in South Australia. Steele’s creation was cast in concrete panels at Mosaic Flooring Co. Ltd in Laurel Park (Croydon Park), an Adelaide branch of Pioneer Concrete Services Ltd that operated on the site now occupied by SA Precast Pty Ltd.

For a local architect to mount such an artwork at a public hospital in a small Australian city in the early 1960s was quite an achievement. And it did gently ruffle a few conservative feathers about town. Disgruntled letters were written to the local press protesting the ‘waste’ of public money (£30) on a piece of oversized concrete ‘art’. This negative publicity left a subtle imprint in the minutes of the Hospital’s Public Relations Committee meeting on 12 December:

Concern was expressed in the fact that extraneous bodies connected with the hospital, such as architects and builders, gave information to the press without reference to the hospital authorities. This question was raised because of recent articles and letters appearing in the press.

The Committee concluded that there was ‘little that could be done’ about the unauthorised media report. No records have been found regarding the Hospital Board’s discussion of the final proposed design for the General Purposes Building, with its special sculptural face – but they must have approved it.

A view of the newly installed abstract concrete mural on the exterior of the Adelaide Children’s Hospital in Adelaide, South Australia, 4 December 1962

Photographer Sam Cheshire documented the artwork after it was mounted on the eastern section of the General Purposes Building.

The remainder of the building was yet to be constructed. This is the only known image showing the entire mural design.

Source: Newspix

‘Largest Sculpture at Hospital’, The Advertiser, 5 December 1962

‘Hospital Sculpture Cost £30’, The Advertiser, 8 December 1962

Source: Original newspaper cuttings from WCHN History and Heritage Collection scrapbook.

The mural and its modernist peers

The artistic merit of Steele’s creation may have been publicly questioned, but in the broader context of 1960s Modernist art integrated with architecture, his abstract composition was progressive and of its time.

The Adelaide Children’s Hospital artwork (1962) was fashioned in the style of sculptor Costantino Nivola. The Italian artist was renowned for collaborating with architects such as the influential Le Corbusier, and constructing large, abstract mural reliefs using a sandcasting process. In addition to commissions for corporate buildings in New York (1950–), Nivola created artworks for schools and a bas-relief for a Children’s Psychiatric Hospital in the Bronx (c1968). Certain motifs used by Steele do show the influence of Nivola.

Around the time Reginald Steele mounted his mural sculpture in Adelaide, William Mitchell (1925–2020) and Antony Hollaway (1928–2000) were producing large, concrete wall reliefs with dynamic geometric designs for Brutalist housing and office blocks, schools and civic gardens in the United Kingdom.

On the home scene, in 1961 James Meldrum (1931–) created a rhythmic bas-relief mural in concrete for Brisbane’s Wickham Terrace Carpark; and Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski AM (1922–94) painted a Modernist mural for the ETA Foods Pty Ltd factory in Renown Park (SA).

The same year Steele’s artwork made its debut, Lenton Parr (1924–2003) sculpted a vertical relief in form-cast concrete for an external wall of the Chemistry Department at The Australian National University (ACT). Also in 1962, Ronald Sinclair (1926–97) created a modular bas-relief for the Long Beach Bathing Pavilion (TAS) designed by architect Dirk Bolt, casting his patterns in moulds made of beach sand. Inspired by children building sandcastles, Sinclair’s design theme was: homo ludens (man at play).

Sculptor Costantino Nivola using a sandcasting process to create a mural relief for Washington Clinics University Building, c1960

Reginald Steele’s mural relief was inspired by the work of Costantino Nivola, who enjoyed a strong reputation in New York as an architect’s sculptor. Steele may have first encountered this artist’s work in the 6th Triennial at the Palazzo dell’Arte in Milan (1936) while he was studying in Italy.

Nivola created his relief sculptures by carving designs into wet sand and then pouring in cement and letting it dry.

Source: Courtesy of Fondazione Nivola and the Nivola family

Dirk Bolt, Bathing Pavilion, Sandy Bay Road, Sandy Bay, 1962

This view of the Long Beach pavilion in Tasmania, which was designed by architect Dirk Bolt, showcases Ronald Sinclair’s bas-relief.

Photograph by Frank Bolt, Neg. 398, Ref. 100918, Hobart Architecture, Image 20.

Source: Courtesy of Paul Johnston, with permission from Tonique Bolt

SJ Ostoja-Kotkowski, Mural, ETA factory, Renown Park, 1961

Photograph by Keith Neighbour, S294/1/21/2, Neighbour Collection, Architecture Museum, University of South Australia.

Source: Courtesy of Julie Collins, University of South Australia Architecture Museum

James Meldrum, Mural, Wickham Terrace Car Park, Brisbane, 1987

Completed in 1961, this image of Meldrum’s bas-relief in textured concrete was captured on 24 November 1987.

Photograph by Richard Stringer, Q 4000, 0987–032.

Source: Courtesy of Richard Stringer

The concrete elegy to industry

Steele’s big creation captured a big Hospital audience. Visible to clinical and research staff and patients in all rooms at the rear of the Outpatients Building, it was perhaps aimed specifically at the north-facing wards on the 7th and 8th floors, where a play room had been situated for convalescent children. The mural sculpture looked directly over the Casualty Department carpark. Thousands of sick and injured children would have encountered the artwork when they were brought in via ambulance.

Reginald Steele was one of the chief architects on the Outpatients Building project. He knew the site plans inside out. He would have positioned his mural sculpture with the children in mind.

The artwork was also composed for the occupants of the General Purposes Building. Steele probably designed this building himself. Having sketched the plans for each room, he was intimate with their intended purpose and contents. He knew his audience: engineers, painters, plumbers, electricians, carpenters – and machines.

Steele was an architect of some 30 years when he designed this sculpture for the Hospital. Its motifs are the abstract language of a man who had drawn 100s of building plans in his life. The larger geometric shapes speak of simplified structural elevations; of roofs in aerial view. The mural design is like a deconstructed, fantastical architectural drawing in 3-D, populated by giant toy maintenance workers with tools for heads. It is a concrete elegy to industry; a platonic love letter to fellow men in the building arts and trades.

Above all, the artwork was playful. The aim of its creator was to bring happiness to young patients, and brighten the days of those who laboured to maintain the built environment to support their healing.

View of Casualty Department carpark, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, mid-late 1960s

The inspector of the Hospital’s Casualty carpark was very familiar with the mural sculpture. He worked long hours in front of the artwork every day.

Ambulance officers unloading a child patient at the Casualty Department entrance, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, mid-late 1960s

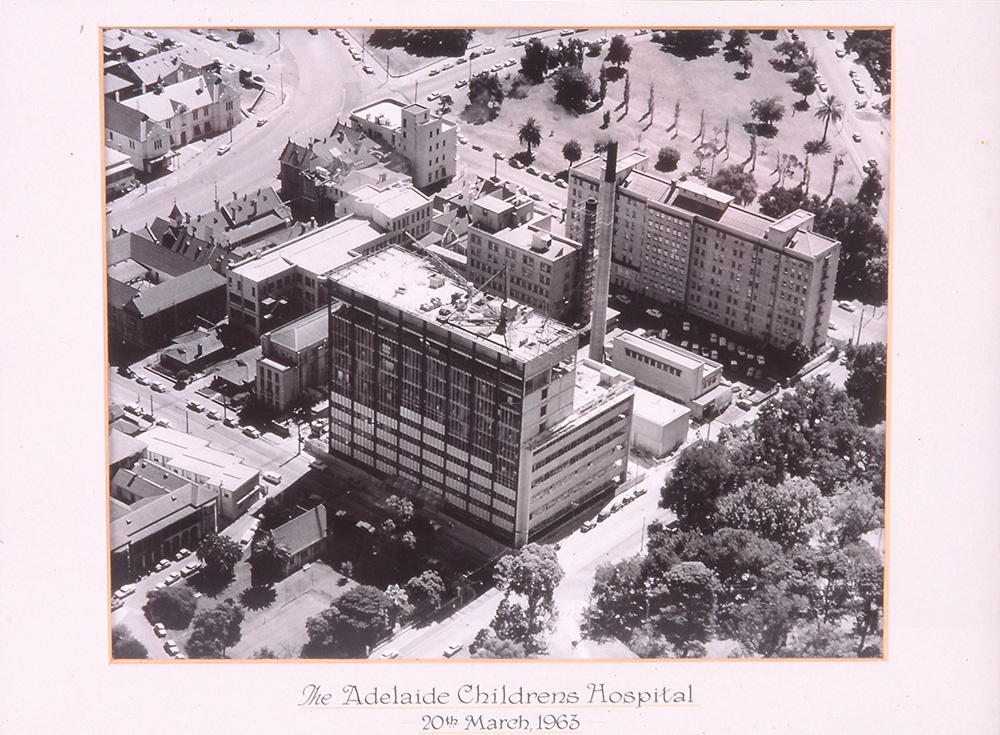

Aerial view of Adelaide Children’s Hospital, 20 March 1963

Opposite the park on Sir Edwin Smith Avenue, a section of the General Purposes Building and mural sculpture can just be seen peeking out from behind the Outpatients block.

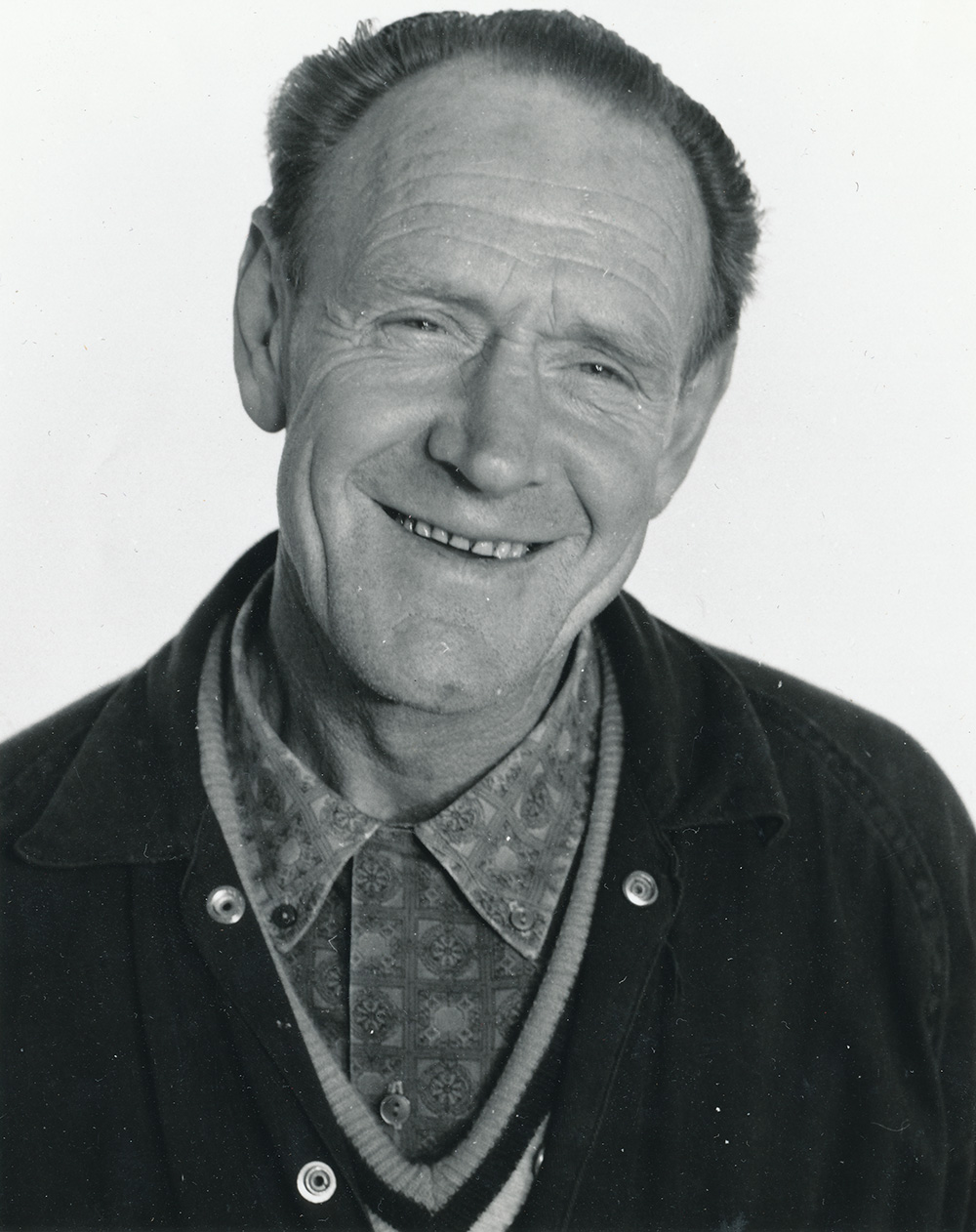

Clem Backman, Maintenance Engineer’s Assistant, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, 1964

In charge of mechanical maintenance, Clem Backman was the offsider to Maintenance Engineer Doug Hawes, who had an office on the first floor of the General Purposes Building just down the corridor from the mural wall.

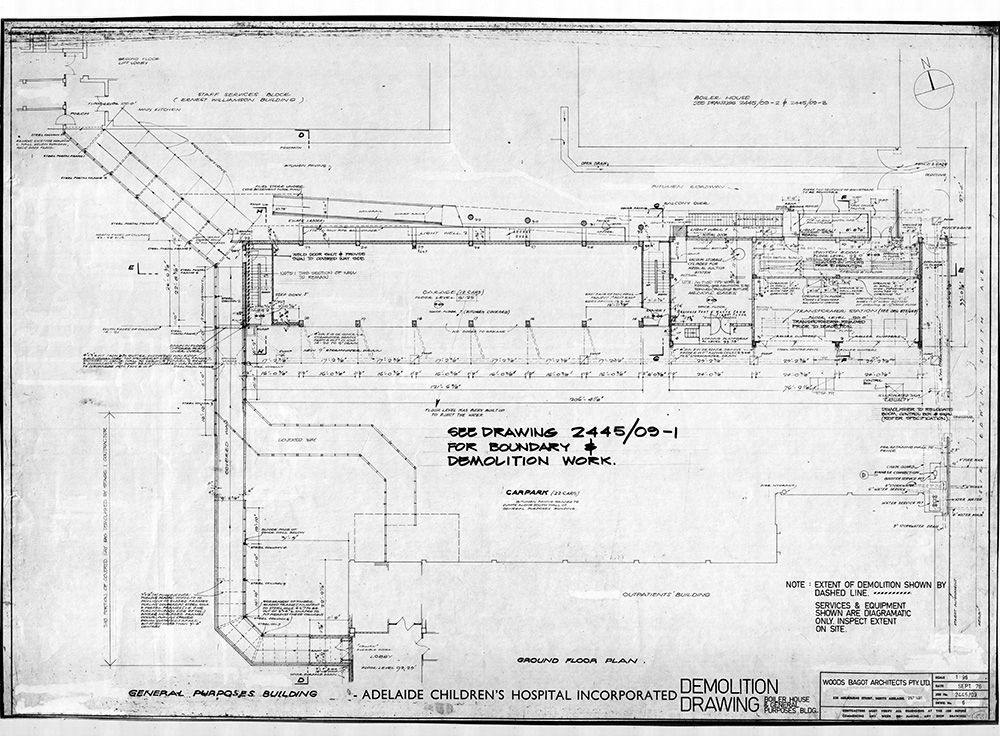

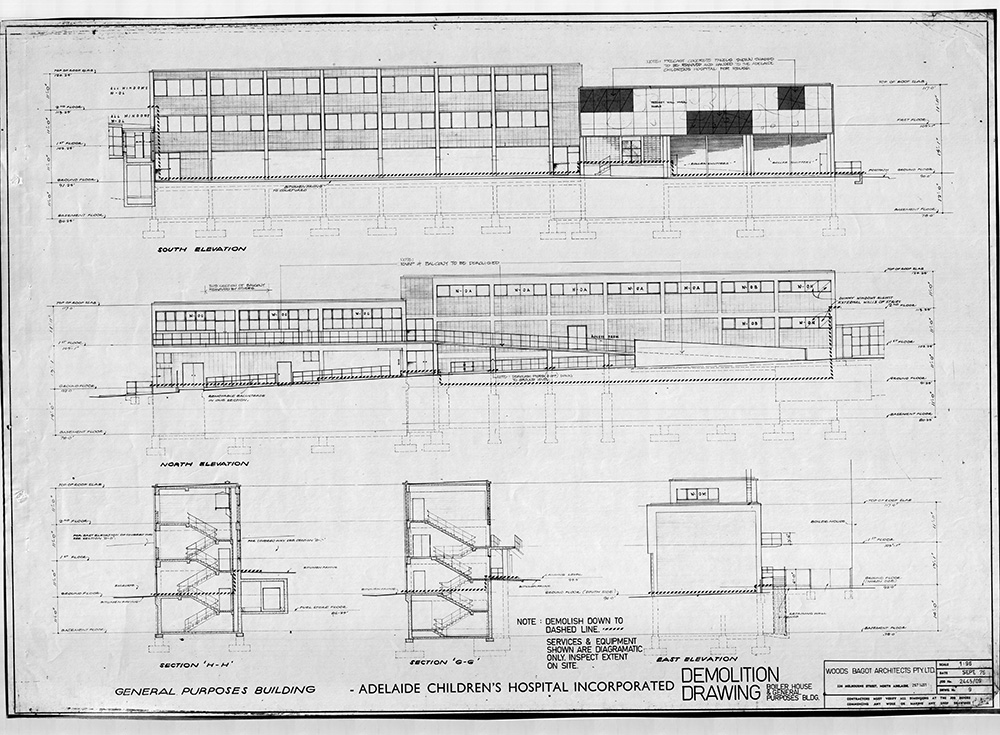

Demolition Drawing for General Purposes Building, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, September 1976

The details marked on this ground-floor plan of the General Purposes Building (GPB) indicate the location of the electrical transformer station, switchboard and medical gases on the ground floor (at right).

The mural sculpture, comprised of a series of Unistrut gridwork panels, was mounted above the roller shutters on level one. The Hospital carpenters, Kurt Erdman, Phil Martin and Bernie Stickland, worked inside the building directly behind the mural wall.

This demolition plan is a revision of an architectural drawing for the original building design, c1960–61. The original date and details of the architectural firm have been covered over and changed.

Plan prepared by Woods Bagot Architects Pty Ltd, Job No. 2445/09, Drawing No. 6.

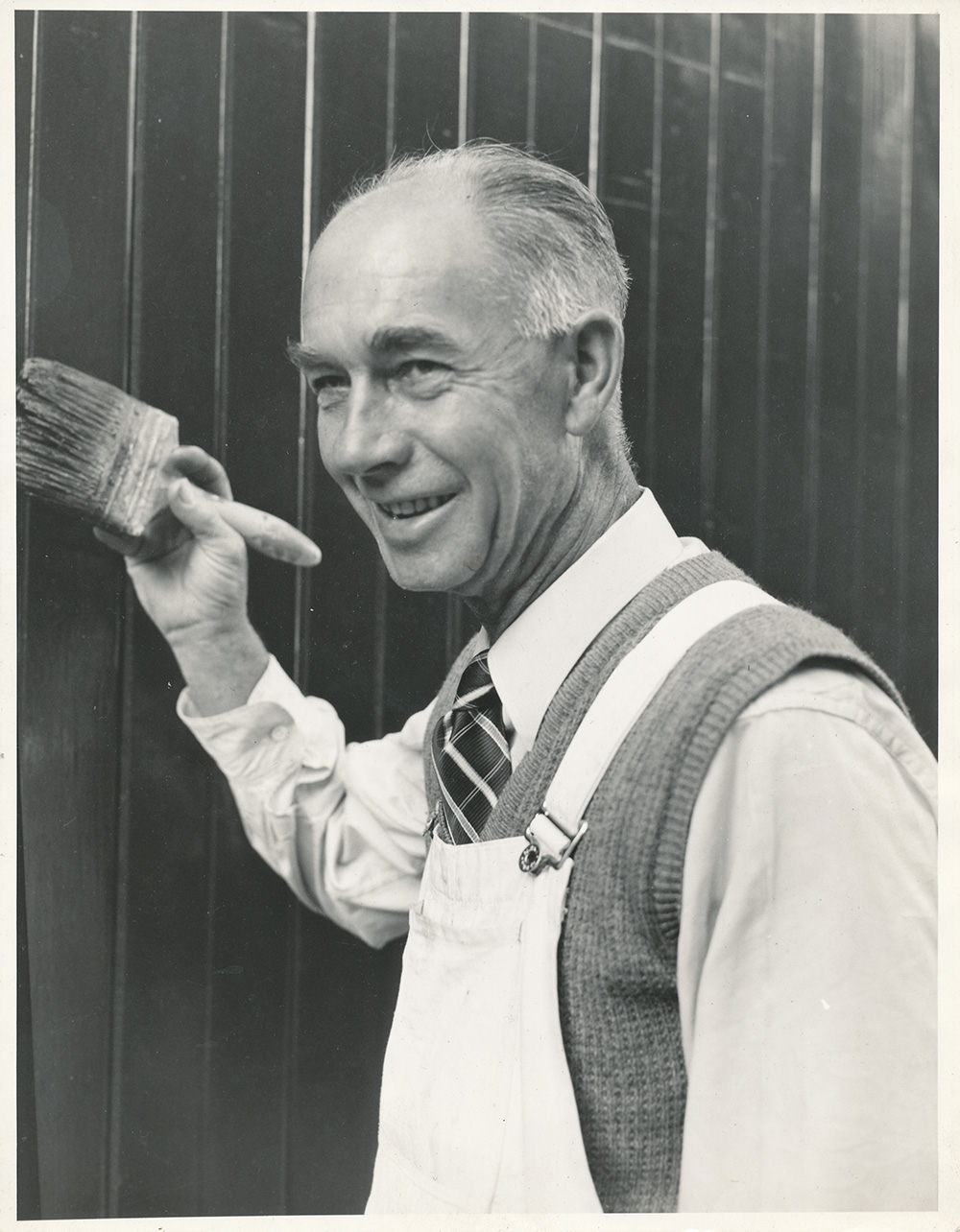

Bill Osborn, Foreman Painter, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, 1958

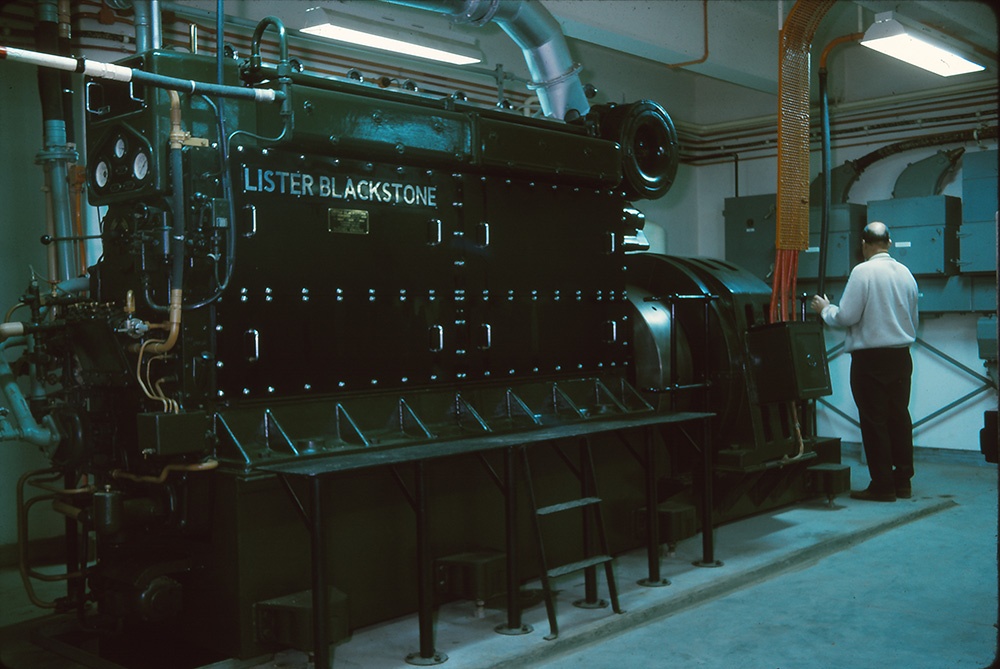

Bill Osborn looked after all paintwork maintenance at the Hospital. Until his retirement in 1965 he worked in the basement of the General Purposes Building, which also contained the Electricians’ workshop and Lister Blackstone diesel generator.

Lister Blackstone diesel generator in the basement of the General Purposes Building, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, mid-late 1960s

The generator is the last piece of machinery retained from the old General Purposes Building. Long decommissioned, it still resides in a basement at the WCH site.

The mixed fortunes/the first demolition

By 1969, demands on Casualty and Outpatients and on bed occupancy at the Hospital were an increasing concern. The SA Government agreed to make funds available for a major site redevelopment.

In 1972, a proposal to make extensions to the Rieger Building was rejected by the City of Adelaide Development Committee, due to concerns about the impact on the local skyline. UK consultants were engaged. Their alternative proposal for a 4-stage development scheme of low-rise buildings was accepted.

The winning scheme placed a major target on the backs of the General Purposes Building (GPB) and its ‘unsightly’ Boiler House companion. These buildings were taking up valuable real estate on land near Sir Edwin Smith Avenue where a new diagnostic and surgery wing was to be erected (the Rogerson Building).

In 1970 the Hospital had received a large bequest from the estate of the late Samuel Saltmarsh. These special funds were now allocated to construct a new energy plant and maintenance building on Kermode Street. This fortune was unfortunate for the Boiler House and GPB. It sealed their fates. Barely over a decade old, they were both about to become redundant.

In April 1976, the demolishers brought down the Hospital’s last industrial boiler chimney. The workshops and machines from the old maintenance building were transferred to the new Saltmarsh Building in October. The workers followed. Leading up to Christmas 1976, the demolition crew returned to finish the job. The newly vacated GPB, with Reginald Steele’s bold mural relief, did not see in the new year of 1977.

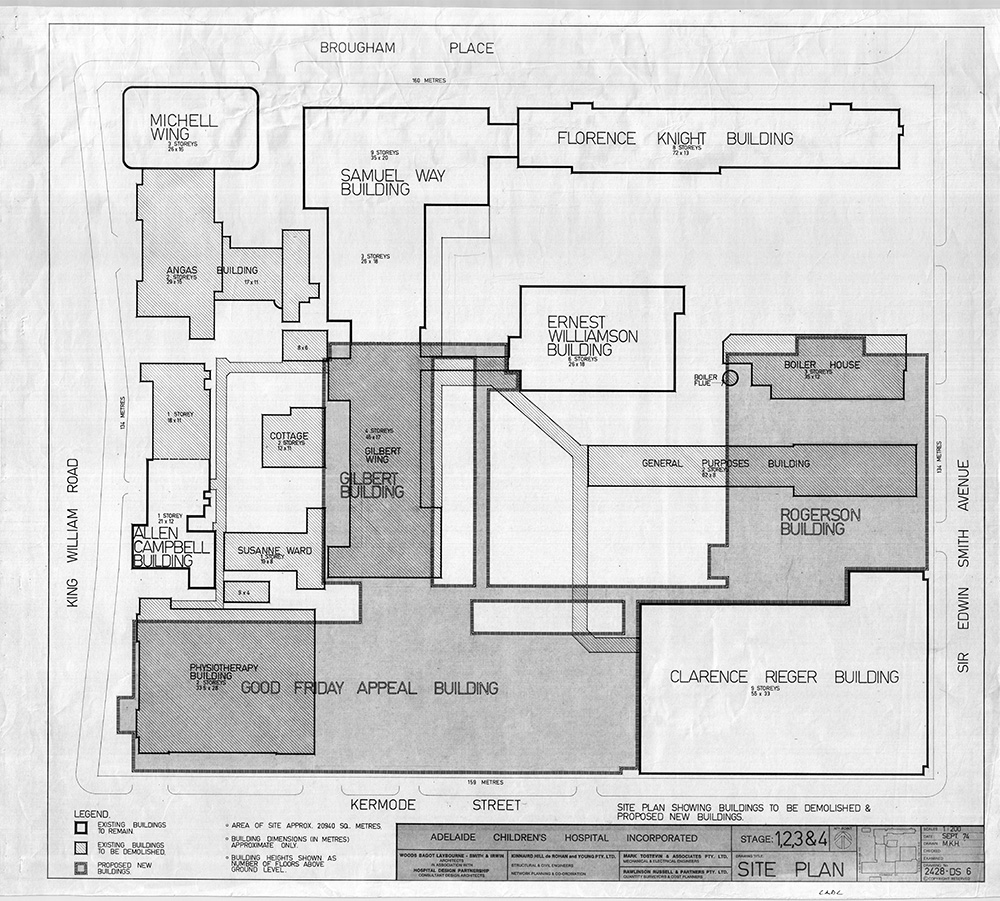

Site Plan of Adelaide Children’s Hospital Showing Buildings to be Demolished and Proposed New Buildings, City of Adelaide Development Committee Submission, September 1974

Plan prepared by MKH of Woods, Bagot, Laybourne-Smith and Irwin Architects in association with Hospital Design Partnership, Drawing 2428 DS6 EO4.

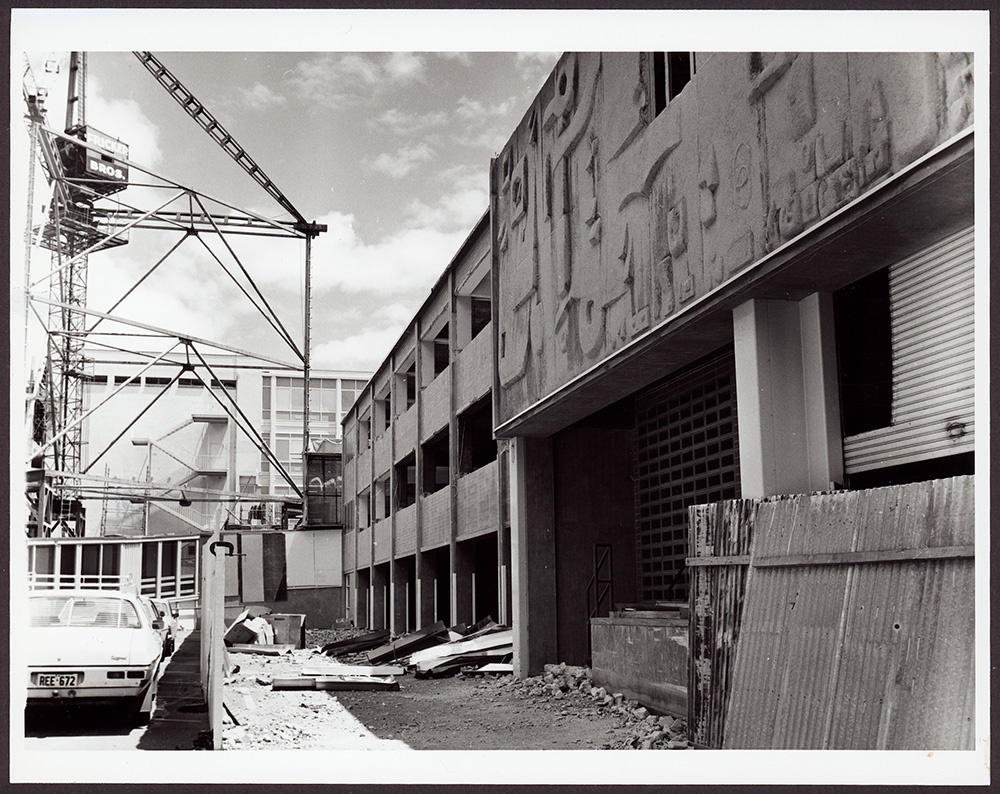

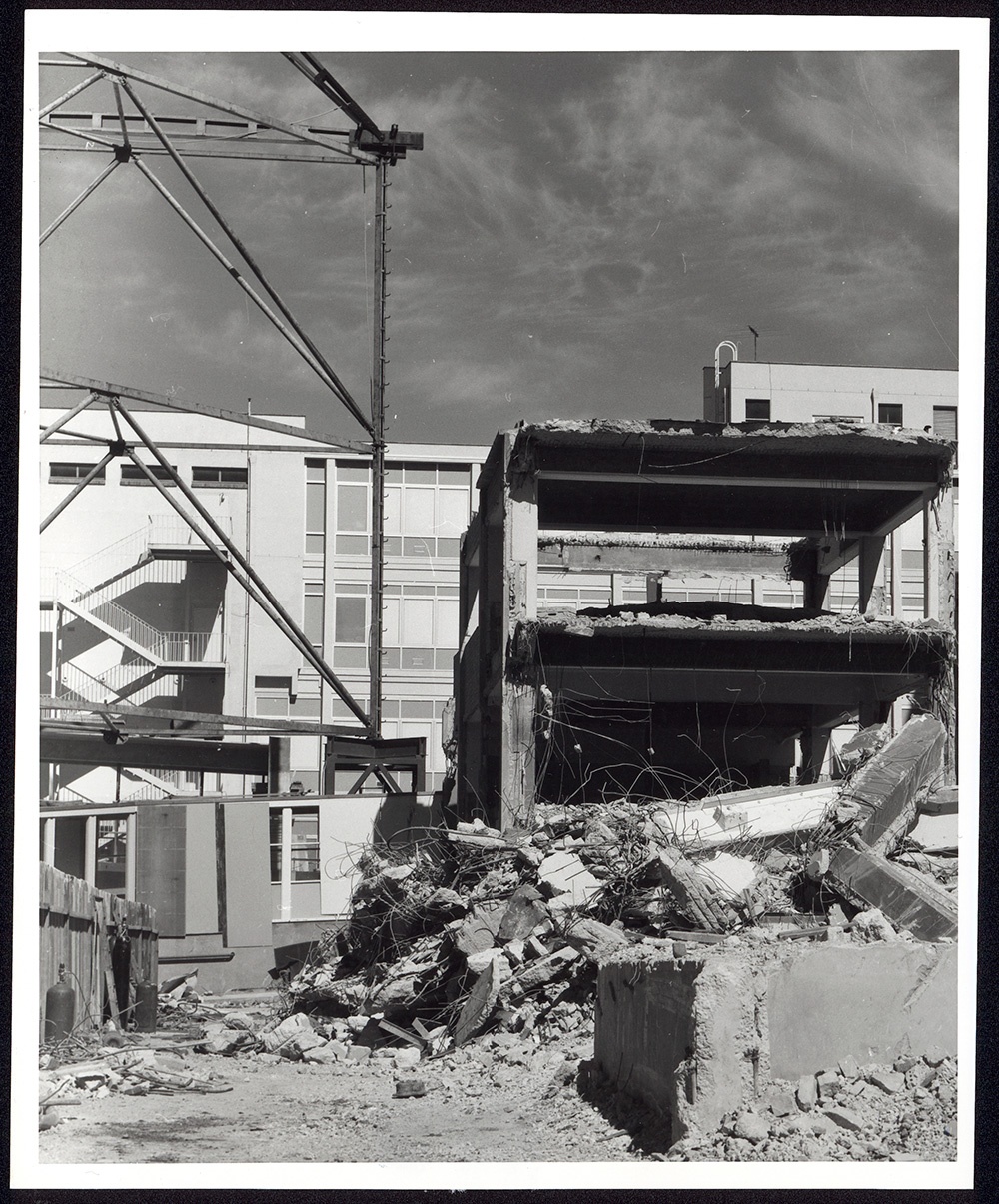

Image of demolition site at rear of General Purposes Building, April 1976

Sir Edwin Smith Avenue, West Side, 5 November 1976

This image shows evidence of some mural panels being dismantled in the early stages of the General Purposes Building’s destruction.

Source: Acre 732 Collection, State Library of South Australia, B 32583.

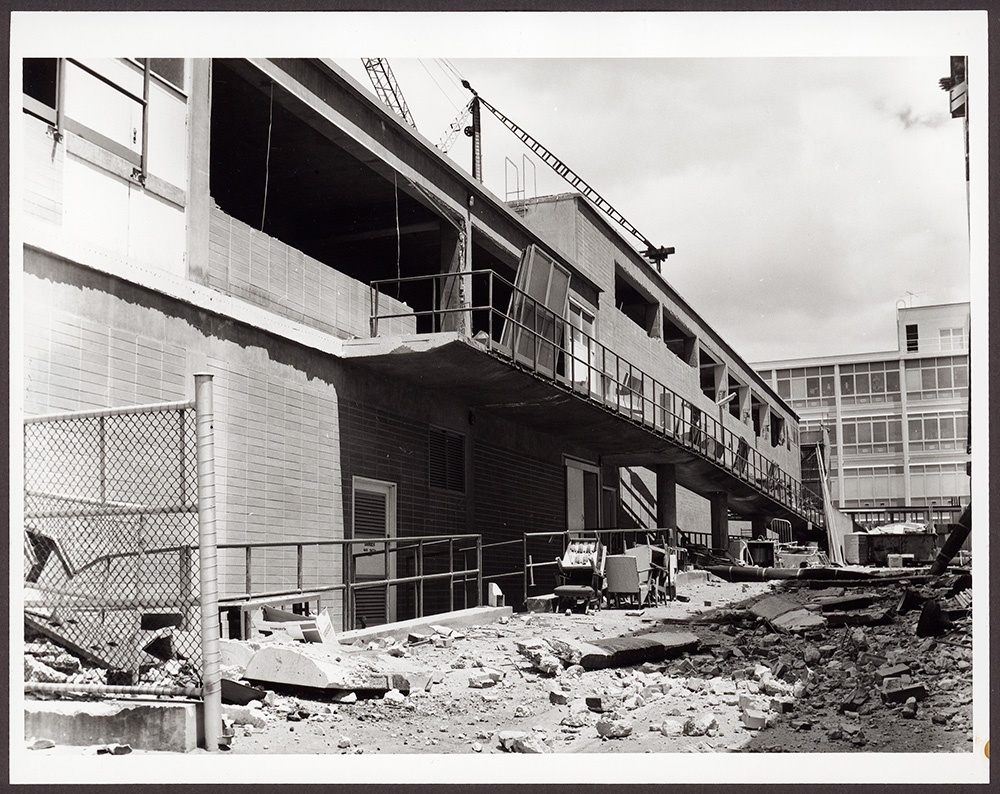

Sir Edwin Smith Avenue, West Side, 5th November 1976

The rear of the Hospital’s General Purposes Building in an early state of demolition.

Source: Acre 732 Collection, State Library of South Australia, B 32587.

Sir Edwin Smith Avenue, West Side, 21 December 1976

The General Purposes Building in an advanced state of demolition.

Source: Acre 732 Collection, State Library of South Australia, B 32676.

The second chance

Two demolition plans for the General Purposes Building were marked with special instructions that the Hospital should retain 11 (non-consecutive) panels of the mural relief for reuse. Because no trace of the artwork can be found at the Hospital today, it was assumed that these instructions had not been honoured.

However, a colour photo was recently unearthed in the Hospital’s Engineering and Building Services Department that depicts an installation of a series of sculptural concrete panels. These are clearly part of the same mural relief.

Eleven panels had indeed been salvaged and reinstalled in a second, reduced configuration. This was ‘concrete’ evidence that the artwork did get a reprieve. Incredibly, the photograph had been discovered in a dilapidation report dated 1992.

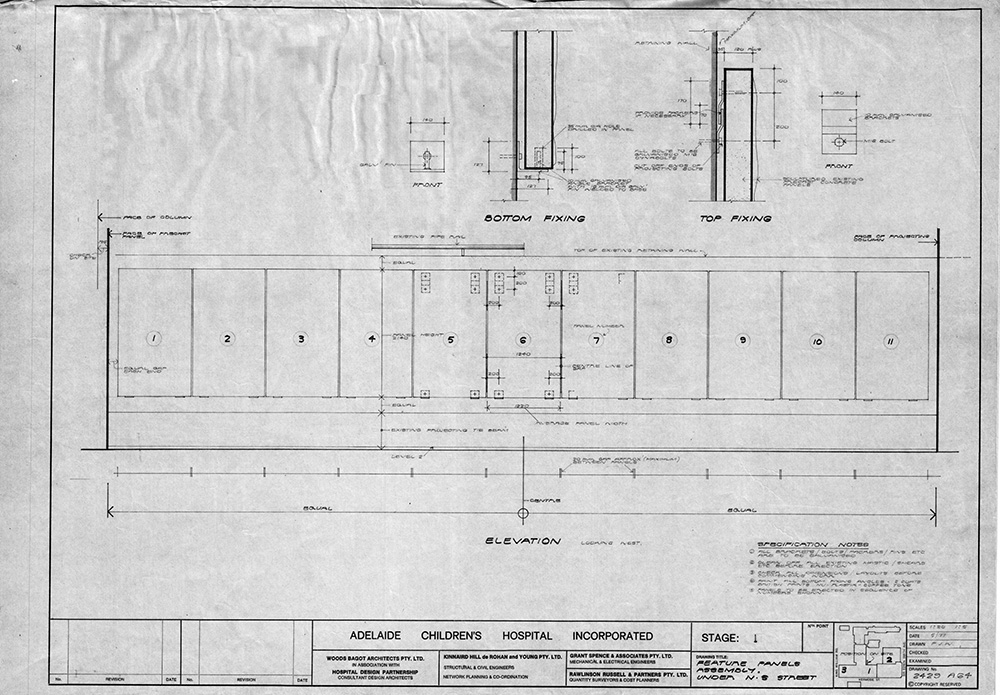

Close inspection of a 1977 plan referring to ‘Feature Panels’ turned out to be instructions for builders on how to bolt the mural pieces along a concrete barrier wall in a new location at the Hospital. This indicated that the artwork was reinstalled beneath a glass-sided walkway called the North-South Street, which passed between the Playdeck and the old Gilbert Wing. The artwork extended along the front of the Gilbert – a building co-designed by Reginald Steele four decades earlier – and was visible from the ‘street’ above.

A lone, dim image in the Hospital’s historical slide collection revealed that the mural’s semi-subterranean location was directly opposite the old school room and creche in the basement of the Good Friday Building.

Demolition Drawing for General Purposes Building, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, September 1976

Adjacent to the section with shaded rectangles is a handwritten request for the Hospital to salvage and reuse 11 concrete panels.

Plan prepared by Woods Bagot Pty Ltd in Association with Hospital Design Partnership, Job No. 2445/09, Drawing No. 9.

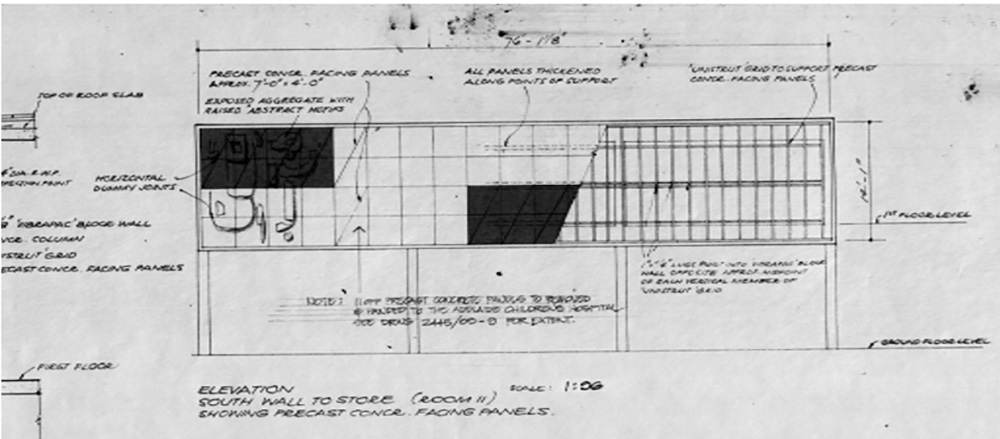

Demolition Drawing for General Purposes Building, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, September 1976

The grid with black shaded rectangles at left – ‘exposed aggregate with raised abstract motifs’ – alludes to a section of the original mural design sketch. This sketch has not been located.

Plan prepared by Woods Bagot Pty Ltd, Job No. 2445/09, Drawing No. 4.

Architectural Drawing for Assembly of Feature Panels under the Adelaide Children’s Hospital North-South Street, May 1977

Plan prepared by PJW of Woods Bagot Pty Ltd in Association with Hospital Design Partnership, Drawing No. 2429 A64.

Playdeck under construction, Adelaide Children’s Hospital, late 1970s

On the far right is a covered walkway with glass sides called the North-South Street. The 11 salvaged mural panels were reinstalled along the Gilbert Building side of this ‘street’, one level below the Playdeck. This would be underneath where the Hospital’s Aboriginal Liaison Unit and Starlight Express Room are located today.

Scene in Adelaide Children’s Hospital school room, late 1970s or early 1980s

In its second life, the mural sculpture was installed opposite the Hospital School in its former location in the basement of the Good Friday Building. Here, abstract motifs on several panels of the artwork in the background are just perceptible through two sets of windows. The staircase between the School and the mural connects this area to the ‘North-South Street’ on the level above.

The Hospital would have relocated part of Reginald Steele’s artwork here for the School children to enjoy.

Section of salvaged mural installed at the second site, 1992

Photograph found in Adelaide Medical Centre for Women and Children Dilapidation Report, Stage 1, 23 January 1992.

The second demolition/the art casualty

In its second incarnation, the mural relief led an undisturbed existence for another decade. Then a major merger rocked its foundations.

On 15 March 1989, the Children’s Hospital amalgamated with the Queen Victoria Hospital. To come together physically, a whole additional hospital had to be accommodated on the North Adelaide site.

Architects were consulted. Numerous site development schemes were conceived and considered. But it was inevitable: some ageing buildings would have to go. The Ernest Williamson Building and the nurses’ home on Brougham Place (the Florence Knight) were both earmarked for demolition to make way for the new Queen Victoria Building.

The old Gilbert Wing had long been identified as ‘time expired’. Of the 4-stage Hospital development scheme approved in 1973, Stage 4 involved replacing the old Gilbert Wing. Though a prize-winning design back in 1933, its structure had not been engineered. It could not accommodate additional floors to expand its capacity. Stage 4 was now given the green light as part of the amalgamation construction project. The Hospital committed to rebuilding the Gilbert from scratch.

In March 1992, the wrecking ball swung again. Old Gilbert was felled. The Hospital’s North-South Street

– the mural’s second home – was gutted to construct a foyer for New Gilbert. Reginald Steele’s artwork saw its final day. It had run out of lives.

Second – and final – demolition of the mural, March 1992

A construction worker (below) looks on as the demolished remains of Reginald Steele’s mural are scooped up for disposal. The site on the left is being cleared of rubble from the old Gilbert Wing.

Forgotten Murals II: Art Casualty of Built History will be on display for the Hospital community and available online for the public to view from 1 May – 26 July 2021 in the Yellow Heart Gallery.

*Please note: Due to COVID-19 there are visitor restrictions in the Hospital. To remain updated on this information visit www.wch.sa.gov.au.